Mountain lions are one of the last remaining apex predators that roam freely in Southern California, and their interactions with humans have been a source of legends for centuries.

When non-native settlers began arriving in Southern California in the late 1800s, encounters became more frequent, and the stories of interactions with mountain lions were often embellished, and some were even humorous.

The name “mountain lion” has become the most popular description for the big cats, but they are known by several other names including cougar, puma, and panther.

Mountain lions are very adaptable, and they have the largest range of any wild land mammal in the Western Hemisphere, stretching from the Canadian Yukon to the Southern Andes Mountains in South America. In the United States, they are generally found west of the Rocky Mountains.

Native Americans respected mountain lions, and they knew how dangerous the cats could be, especially when their normal prey was in short supply from drought, fire, or other conditions. Interactions between Native Americans and mountain lions were less likely than with early European settlers, because the native tribes didn’t raise animals as a food source that would attract the cats.

California ranchers were particularly wary of mountain lions, because they were known to attack and kill cattle and other livestock. Occasionally, a mountain lion became so aggressive toward livestock, that a bounty would be offered for the animal, and hunting them became a regular sport.

In January 1877, the San Bernardino Weekly Times newspaper advertised mountain lions as one of the many types of game that could be hunted while staying at the Crafton Retreat, in the eastern foothills of the San Bernardino Valley. The article noted: “the more adventurous Nimrod [skilled hunter] can be accommodated in the canyons and higher hills by more royal game, such as deer, and – start not, ye Eastern sportsman — mountain lion.”

In the late 1800s, game hunters across the west began to boisterously advocate for the killing of mountain lions to preserve the population of other game animals. Hunters and others who relied on game, claimed the cats killed large numbers of deer and antelope in the local mountains.

In 1899, San Bernardino County began offering a $10 bounty for the scalp of a mountain lion, and the figure increased to $75 by 1928. By the early 1900s, California counties were typically offering a $20 bounty for a mountain lion. The bounty continued statewide until 1963, and it was ended in San Bernardino County in 1967.

One of the most exaggerated reports of a lion encounter was reported in the Los Angeles Times on July 5, 1895, in an article stating: “a huge mountain lion measuring 12 feet from tip to tip” was killed in Arizona.

Historic records tell us the largest mountain lion on record weighed in at 276 lbs., and their average weight ranges from 75 to 200 pounds. Average length from nose to tail-tip ranges from 6 feet to 7.5 feet.

On the light side of the interaction spectrum, a report in the Los Angeles Evening Express from Feb. 17, 1890, stated; “Henry Ems of Altadena, whose home is at the foot of the mountains, ran across a mountain lion a few days ago. Ems waived a valise [small piece of luggage] at the brute and the latter couldn’t stand such a modern salute, turned tail and fled.”

Another non-terrifying encounter was reported in the July 1, 1901, issue of the San Bernardino Daily Times-Index, describing the pursuit of a mountain lion in Wrightwood by local rancher/miner S.S. Guffey.

After tracking the animal up a canyon, Guffey fired two shots at what he presumed to be a big cat perched in a tree. The “cat” turned out to be a sack of clothing and personal items that belonged to a local miner. Only slightly embarrassed, Guffey turned the sack in to the local sheriff’s office.

As noted by Guffey’s experience, mountain lions don’t necessarily need to be on-site to be vilified.

In September 1901, a Mrs. Switzer was riding her horse up Waterman Canyon Road in the San Bernardino Mountains, when she thought she saw a mountain lion peering at her through the brush. She pulled out a pistol for protection, and ended up shooting herself in the leg during the commotion. The cat was never actually seen, but Switzer stuck to her story.

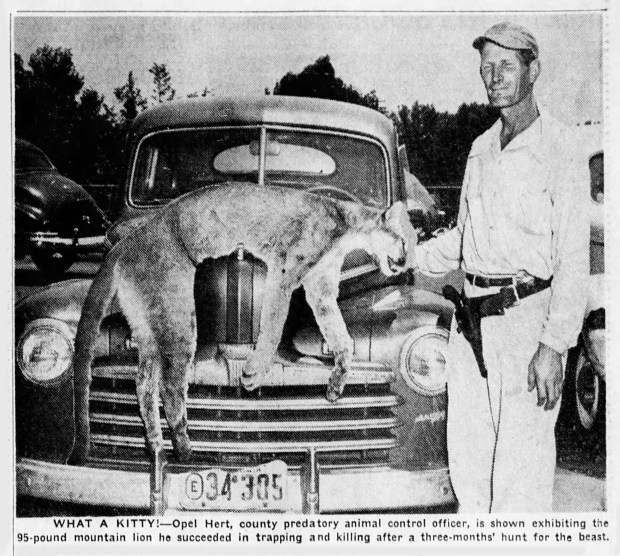

In 1942, mountain lions were still an issue, and San Bernardino County reported their predatory animal control officer had trapped a 90-pound cat above Etiwanda. The trapping was the 18th capture in his official capacity, and his 87th overall.

Reports of mountain lion interactions have remained steady over the years, but most were nothing more than frightening experiences for the humans, and presumably for the cats. Attacks by mountain lions on humans are rare, and fatal attacks are extremely rare, based on the size of the human population that could interact with them.

The earliest recorded fatal mountain lion attacks in California occurred in 1890 in Siskiyou County, with the death of a 7-year-old boy, and in 1909 in Santa Clara County with the death of a young woman, and a 10-year-old boy. The next fatal attack didn’t occur until 1994, when a woman was killed in El Dorado County. There have been six fatal mountain lion attacks recorded in California.

Mountain lion bounties in California ended in 1967, and hunting was stopped in 1970. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife provides estimates from two studies that show ranges of 2,000 to 3,000, and 4,000 to 6,000 mountain lions living in the state today.

In 2012, an adult male mountain lion was discovered roaming the Hollywood Hills, and he was captured and fitted with a radio collar for study. Designated as P-22 by wildlife officials, the cat gained celebrity status by living in a small rural island surrounded by a dense urban population.

Officials believe P-22 was struck by a vehicle in December 2022, and he was captured for a health check. It was determined that P-22 had significant health issues in addition to the injury, and he was euthanized on Dec. 17, 2022.

A memorial service for the revered cat was held earlier this month at The Greek Theatre in Los Angeles, where thousands came to honor the mountain lion that captured our interest.

Mountain lions continue to roam the wildlands surrounding Southern California, and their occasional ventures into urban areas and interactions with humans and their pets are still notable.

In recent years, California has constructed several major wildlife crossings that will let wild animals cross major thoroughfares safely, allowing them to continue to be part of our human/wildlife history.

Mark Landis is a freelance writer. He can be reached at historyinca@yahoo.com.

Source: Orange County Register

Be First to Comment